Near to the Next Paradigm

The Metaverse, the Singularity, and the Rest of Us

Imposter syndrome is not considered a genuine medical diagnosis, and yet I suffer the worst case of it. I never thought of myself as a great writer. I was, and am, afflicted with obsession, which was attendant with the ADHD. That’s also dismissed as a fake disease, yet I had all the symptoms: obsession, hyperfocus, distractibility, disfluency, impulsivity, panic attacks, anxiety, and forgetfulness. The hell its fake. Maturity helps a lot, but it never gets fully untangled. Nowadays, with all my effort, I try to see it as something of a superpower, while keeping in mind that to romanticize the condition is to imply, insincerely, that we’d all be better off with the diagnosis. Peter Gray buttresses the point, explaining how creativity is a positive side effect of ADHD. “Divergent thinking” is the shorthand. The talent is not so much in solving problems, but rather finding problems. It’s the endless line of questioning – “why-why-why,” the grip of adolescence – and trying not to be afraid when you begin seeing patterns.

Inquiry, I think, fulfills at least one journalistic essential. As for the other part – presenting one’s findings – it has often allowed another person’s eyes to be jolted open, because I’ve just revealed something amazing. I was good at this, even if it wasn’t so much my specialness but because so many live in a mental box – one that I’ve glazed into. The accursed part that came with it was an internal monologue that rarely shut up. All those long walks that allowed endless mental ramblings to cycle through the badly-knotted neuro-wiring. As of late, I feel that the voice has shut up. It’s become eerily quiet. I search Hoffer’s diary, and am relieved when I come across this entry:

The fact that I accomplish little when I take time off disqualifies me as a writer. I do have an original idea now and then. If I hang on with all my might, I eventually put together a few thousand words. It may take a year. I lack a flow of words. The most crucial words are never at my service. I have to search and recruit them anew every time.

In another entry, Hoffer wrote: “The weakening of my memory frightens me. Unless I note a thing down it slips my mind completely. The effort to remember what I forgot results in actual pain.” That was in 1959, when Hoffer was approaching 60. As I inch closer to 40, I sympathize with the loss of mental acuity, the actualization of agony, like its right there in that sinus-infected forehead (maybe some sinus rinses would help me out; hey, there is a connection!) There’s been a lot of recent talk about cognitive decline, what with a president who doubtlessly suffers from it, and a former president who likely does as well. Maybe dementia will eventually find its way onto the list of fake ailments, that as a pushback against all those raging paranoically about it. Doubtful. There is something very harmful taking place. I have my guesses.

My previous obsession was the realization that none of this was worth it. Why, I’ve concluded, do I even bother? “Hundreds of thousands of words,” I fume. “Fifteen years,” I repeat, often beating my fist against the steering wheel. “It’s gotten me” – as I regret to recognize – “nowhere.” No readership, no money. Now I face the paradox of trying to please an online audience while also ridiculing the entire notion of such a thing. Resultingly, my latest obsession stems from the last, now implicating the internet as a whole. Planet Earth is being entangled in the World Wide Web. I wonder if that was my problem all along, wanting to be “free from the influence of other people’s attention,” as Freddie DeBoer recently put (whose essay I’ll come back to). The dilemma before me is how to find an audience and get paid for it without being stuck inside the screen.

This problem seems far more serious once you’ve seen online folk say that they know someone “IRL.” In – Real – Life. A depressing acronym that shows how quickly the Metaverse is being pulled over us. Prior to this era, that was the only way to know someone. In the Data Age, so many relationships are phony, like so much else. Fake friendships and the ensuing fake feuds. We now witness a general blunting of society.

I remember when I was in prison: The picture of a tree in a magazine could bring me to tears. My senses were deprived. I smelled no sweet air, saw little that was vibrant, tasted hardly anything delectable, and rarely touched anyone. When I had any of these, the faucets turned on. Even the feel of blood dripping out of my nose, the result of an angry knuckle, reminded me of my humanity. Somehow, a part of me misses that deprivation, as it could be the only thing to reilluminate a soul gone faded. Now, everything is on the Screen.

Scariest of all, as I type this in the year 2024, much of it isn’t even an actual picture or video of something real. We see a majestic waterfall or a beautiful face, and the first thing we ask: Is it AI? We are hypnotized by a mimesis, a simulacrum enveloping us, now almost totally enthralled by a pixelated prison. Online, we can be bombarded by the most disgusting pornography, yet in the real world we have declining birthrates and far fewer young people having sex. We have fingertip access to so much information, but are handicapped with diminishing experience and very little understanding. My God – young folk aren’t even driving anymore! Only 40 percent of 16–19-year-olds have driver’s licenses, down from 64% in 1995.

What paradigm have we slumbered into?

As for the journalists, the most well-known should be seen as the new Talking-Heads, those who sit in front of their screens, playing video games while another monitor feeds them the news, and then giving their “hot takes.” And that’s mostly what they are: extended hot takes. They don’t crack books. They don’t read the papers. They certainly don’t travel anywhere to get a firsthand account. Most of the interviews are with others who get their information in the same way. Interviews with big-name scholars or policymakers will make online waves. That’s “online journalism” in a nutshell. They’re starting to resemble a lot like these AI programs, just digesting and interpreting what’s inputted to them.

“No editorial writer ought to be permitted to sit in an editorial room for month after month and year after year, contemplating his umbilicus,” wrote Mencken. “He ought to go out and meet people.” Incoming cliché: If only we could read what that curmudgeonly man of American letters would’ve written about his heirs. Yet what is produced every minute of every day amounts to incomprehensible magnitudes. One could never “consume” it all. Orwell and Thoreau both have Wiki-entries devoted to single essays, those which could be read in an hour or two. The top influencers of the Digital Age do multi-hour shows every single day. Who, or what, will receive the prestigious Wikipedia entry? The aspiring “content creator” might ask: Why even bother?

I don’t mean to call everyone an idiot or clout-chaser. Some of their work can pass. Much of it merely fails to break new ground. Look at the latest interview between Chaya Raichik (Libs of TikTok) and Taylor Lorenz. Although I appreciate Chaya’s publicizing the madness that is transgenderism, her unimpressive performance epitomizes the type of journalist I’m referring to. She had real difficulty in articulating the reason why the illogic of transgenderism leads to harm. Still, that Twitter check comes through. Lorenz is wrong on the issue, yet at least she gets out there and interviews people. Even more to her credit, she said something interesting in an interview given last year with Quill:

The biggest change is that online culture has just become mass culture. There’s no separation. In 2009, you were online or offline. It was very desktop oriented. YouTube didn’t even have a mobile app back then.

That’s getting close to the point I’m making. Everything can be done via the small computer that never leaves your side. The coupling is nearing completion. Take a look around, and you’ll notice few others taking notice of anything. Their faces are retina-deep inside their screens. They move slowly towards you while blissfully unaware of anyone else around them. “Oh!” they shriek just before the moment of impact. Be thankful if you even hear an “excuse me.” I count the number of times throughout the day that I have to honk at the car in front of me because the driver has failed to look up and see the green light.

What are they doing on their phones? I ask the emergent God that is Google. First hit brings me to a website called Qualcomm, which did a large poll of iPhone users. Number 1 is Internet browsing. 4 is social media use. Number 2 lists phone calls, making me question the whole page. Another website is called Gadget Cover. Ah, there’s the answer I’m looking for: number one reason given as to why people are on their phones – text messaging. (Number 3, is “Facebook,” the platform where I have built up a community of internet friends)

Either way, the citizenry has fallen into a trance. And I say that from the vantage point of no high-horse, as I’ve also become a victim. I am an addict, which many ADHD patients can attest to. So maybe I suffer imposter syndrome because I’ve tried so hard to work inside this phony reality. “Here” – the nonphysical, digital domain. “Cyberspace,” as they used to call it. The US government gave it life, lost control of it, and has been trying to lasso a regulatory piece of legislation ever since. Disappointment is something I share with the folks at the NSA. However, unlike lots of others, I don’t make a profit from my time spent in front of the Screen. Inner monologues are what makes us thinking humans, but they’re no match against the data stream which drowns them out. It leaves a dearth of focus and critical thought. Why do I need to have conversations inside my head when I can listen to the collective dialogue taking place on the internet? Is any of it at least interesting? Well, that’s the very art and craft of Big Tech.

But I resist! Or, I’ve been wanting to. And now I know I’m not the first one to do so. For instance: Johann Hari’s last book was called Stolen Focus, dealing with the neurological damage caused by the screen. Dr. Phil sees screentime as one of the main problems families have to face. There was a 2017 documentary about the minor resurgence of typewriting. And there’s a bunch of new gizmos and apps intended to free us from distraction. All of this, in part or whole, is a pushback against the Digital Age.

There could one day be a more violent pushback. Freddie DeBoer wrote a really great essay, “Ants in the Server Racks: Notes on Someone Else’s Manifesto.” The brilliant piece is one of the most important I’ve come across (and I kick myself because I’m not as thoughtful, creative, or well-read as DeBoer). He’s already seen me coming, explaining how the digital realm is blanketing over human reality:

Rather than make friends at elementary school, they’ll stare into screens; rather than have study sessions with people in their classes, they’ll stare into screens; rather than sweat through awkward but exciting Tinder dates, they’ll stare into screens; rather than have sex, they’ll stare into screens. This all seems entirely likely, to me, and very bleak.

DeBoer thinks a violent pushback will likely take place in the near future, as many others must also see the damage caused by the Digital Culture. Soon, their shouting will turn to outright revolt. “My basic contention,” DeBoer writes, “is that a movement like this could flourish in large measure because we manufacture more and more of them.” By way of steady recruitment, one or more organizations will come into existence. Whether alone or in alliance with each other, they will then try to destroy the very real infrastructure that sustains the Digital Realm. DeBoer is anticipating lost and angry guys – like yours truly. Him and I both know any such movement or organization is doomed to fail.

Rather than go to such lengths, why can’t we – you know – just put the damn phone down, put the laptop in the drawer or closet? Its more discouraging every time one voices these concerns. They’re immediately greeted with an accusation of hypocrisy: “But you’re telling me this using an iPhone; you’re Tweeting, while publishing your articles and videos.” These people appear as a drug addict whose been stumbled upon between two dumpsters, angered and ashamed yet ready to charge others with also having an addiction. How to even begin changing minds so enraptured? The device is the vice! And like slot machines, it requires no external chemical. It’s all so difficult, as occurred to me during a recent walk. (Walks are a good way of trying to jumpstart the mind and get it to wander).

A couple weekends ago, I went to an unfamiliar trail, a paved bike path, situated around and underneath a heavily urbanized area (not in the mountains, or off any beaten paths). I found my way off the path, into some of the bushes, by a small pond. I eventually stood on a slightly elevated perch, where I surveyed my surroundings – over the path and onto the streets that weaved through it. The infrastructure was all around me: the wires, the towers, and the digital billboards that advertised the newest tech. Only the sight of someone trying to ride their bicycle while tapping or scrolling away on their device would have completed this dystopic scene. That person will come; then again, why ride your bike when you can just put a headset on and pretend you’re in a motocross race? Indeed, investigative journalism of the future could simply be going outside and looking towards the sky. Those who do might be paralyzed by the fear that nobody has eyes on you, even as you’re being examined and analyzed at all times.

On my walk, I came across a revolutionary manifesto, graffitied on a park bench (The Park Bench Manifesto): “Fuck what they say. Kill them all, AND Burn it all down. I’m coming for you.” Below the uninspired words was the Anarchy symbol. As the Internet likes to say, I have a lot of questions. How many vagrants, homeless, and impoverished are in possession of an iPhone? Definitely some. Was this the rant of a homeless man who was angry that the government stopped paying for his phone bill? Was he voting for Trump, Biden, or None of the Above? Or was DeBoer’s imagined revolution already underway, right here in Maricopa County? Who knows.

As I see it, Big Tech is creating the hardware. Governments are providing the space for it to flourish. Transhumanistic gurus are persuading us that it’ll make our lives better. I could be wrong in that assessment, but then, that too comes with being human. We see an imposition like nothing that has ever come before. It gets near completion, but there’s still a few more wires needing to be plugged in. For all of DeBoer’s intelligence, he pushes the wrong buttons when describing the Singularity. “The notion,” he writes, “that artificial intelligence will soon learn to make itself smarter, do so recursively, and emerge as a supremely intelligent being.”

Surely, DeBoer knows this definition is incomplete. The Singularity is more than Superintelligent AI. Hollywood plots have already revealed the plans. Up until this point, I’ve been describing something akin to the Matrix: human beings who live in a simulated reality which is ruled over by some greater intelligence. But that “intelligence” is not the machines from The Terminator. Those villains (aside from the “reprogrammed” good robots), as DeBoer would have it, are the result of AI achieving sentience. Rather, what we should be expecting is the villain from Robocop 2. In that film, the bad guy drug kingpin, Cain, had his brain implanted into a monstrous killing machine. Arnold’s killer robot was incorrectly referred to as a cyborg. Nigh, it’s the merging of biological matter with that of omnipotent data.

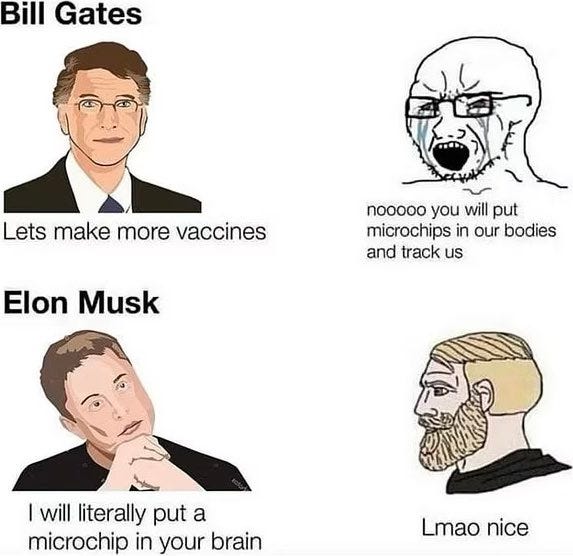

DeBoer doesn’t look to have much of a presence on Twit…err, that is, X. The platform’s owner, Elon Musk, has given himself the appellation of “Mr. Humanity.” He’s also a champion – if not the champion – of the Singularity, which would disqualify him. During a discussion between Alex Jones and David Icke, they were joined by one Adrian Dittman, whose voice and manner of speech sounded exactly like that of Mr. Musk. (Was it really Elon? An AI avatar? Who knows.) Dittman’s prediction was chilling, and I feel it’s one that Elon has made himself: “We’ll first implant computers into our brains, and later we’ll implant our brains into computers.” Elon doesn’t need the fact downloaded into his brain: at that point, we’ll no longer be human.

Elon isn’t merely pipe-dreaming. As founder and owner of Neuralink, he’s all-in with these advancements. In fact, Elon just announced that their first brain implant recipient has made a full recovery. Our gleeful, unnamed patient – just call him Cyborg Zero – can now operate a computer mouse using only his thoughts. (Who knows, perhaps that was Adrian Dittman). Using his platform, Elon pacifies the Rightwing by opposing vaccine mandates, illegal immigration and gender affirmation for minors. For that, the online pundits give applause while keeping their mouths shut about the rest. Forbes tells us that Elon isn’t even submitting any of this research to independent review; he’s just Tweeting – X-ing? – the updates. How long before members of his X-Sphere volunteer?

The only hopeful part here is that the whole thing is so obvious. Someone aged 25 might welcome brain implants. A decade or two in the future, nearing middle age, they’ll be laying on a gurney in the operating room, waiting to find out how that fifty-thousand-dollar device will change their perspective. They’ll be on their iPhone 50, typing a message about how, upon waking up, their next message will be sent with a mere thought. Before those surgeries, the gurus will assure us that such technology will cure us of ADHD and dementia and all the harms that human ignorance has caused. Such begins a new paradigm, one that is dreadful, tyrannical, and inhuman.

I, for one, think we should be free to make mistakes and to improve upon them. We should be allowed to search aimlessly, to love recklessly, and then to one day die, leaving behind only our children and journals and old wooden desks. Will that still be possible? Optimism has never been my forte, and I suspect worse things await us. In what decade, I wonder, will parents start demanding the right to implant chips into their kid’s brains; or, going to the theoretical limit, transfer the whole noodle into a large, shiny machine? That’ll be the only upgrade a young brain will ever need. I’m sure some tech scholar has already pondered this, as originality is increasingly hard to come by. Such is the age in which no information is ever kept inside your skull.

A very well written piece.